Tape saturation is one of the most recognizable qualities of analog audio. Digitally, it can be recreated through controlled distortion curves that mimic how magnetic tape compresses and colors sound.

The character of Analog Saturation

Audio signals interact with the physical limits of the recording medium when they are recorded to magnetic tape. When you increase the volume of an audio signal, you are forcing the tape to hold more energy than it was designed to hold linearly, therefore creating soft clipping and harmonic distortion. Soft clipping creates a perceived warmth, reduces transients and reduces the dynamic range by slightly compressing it.

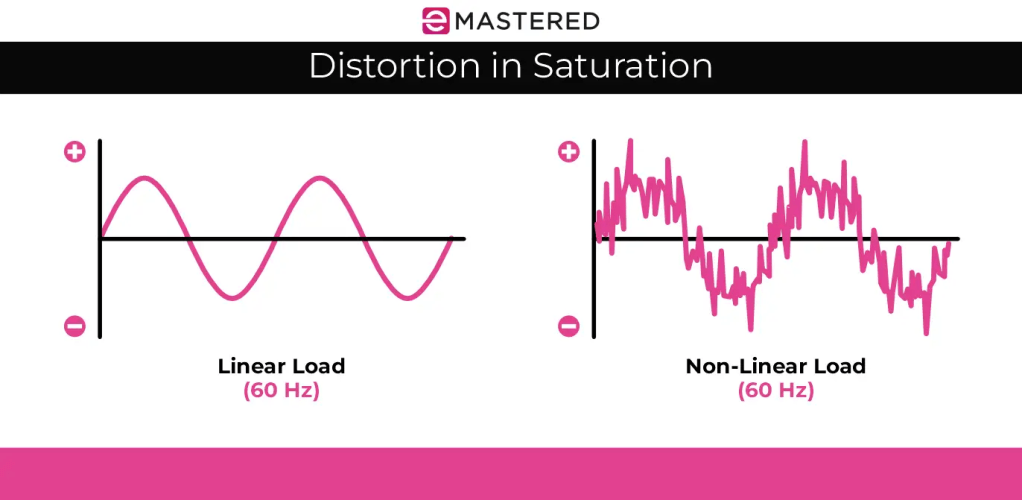

The three main variables that determine how the tape will distort the audio signal based on frequency are bias, tape speed and oxide formulation. Tape bias determines the amount of distortion the tape will produce in a given frequency range. Tape speed and oxide formulation also determine how the tape will distort the audio signal. The main difference between tape distortion and digital clipping (whether hard or soft) is the way in which the distortion occurs. Digital distortion produces sharp, abrupt changes in amplitude while tape distortion does so at a much more gradual rate. It is this gradual change from one amplitude level to another that makes tape distortion have a musical quality and a forgiving quality.

Modeling Warmth with Math

This type of distortion is modeled in software with “polynomial” or “curved” distortion equations—equations which describe how the voltage of an incoming audio signal is modified (and therefore how its frequency content is altered) based on a set of mathematical relationships. For example, if we define our input signal as x and our output signal as y, then we could use a third order polynomial (such as a cubic function):

y = x – ax^3 + bx^5

Where x is our input signal, and the third and fifth degree terms create additional harmonics in our output signal that are similar to those created by analog distortion. By adjusting the values of a and b, we can control how much the curve bends or compresses the peak amplitudes of the input signal.

By adding high frequency roll off and/or slight levels of random noise to the emulated distortion, we can add additional realism to the distortion by modeling the mechanical aspects of the tape itself (i.e., the way the tape rolls back at high frequencies and adds a small amount of hiss). If used very subtly, these types of models provide a richening harmonic quality to a mix while maintaining clarity, thereby bridging the difference between the precision of digital technology and the imperfections of analog equipment by transforming mathematical non-linearity into musical textures.

Reflection

The digital system is able to replicate the dynamic nature of the analog systems through the application of polynomial distortion curves with gentle curvatures and thereby produce a sound that feels authentic, lived in and true to the original performance. Tape saturation is not simply nostalgia but rather demonstrates how simple mathematical formulas can be used to produce a sonic quality that is similar to a human performance.