Part 3 of Research Blog:

Analyzing listener responses from my AI melody generator project revealed more than just accuracy metrics. It showed how people perceive musical intent even when the notes come from a machine.

Background

In the previous Research Blog Post (#2), I explored whether a created by AI melody will be perceived as “human” in terms of phrase structure and tone. I ran the tests for my model with a producer’s survey (40 producers) and asked them to rate both human composed and generated by AI samples based on their musicality, emotion, and level of engagement.

My objective was to assess not only the performance of the algorithm, but to understand how humans interpret artificially creative music if they are unaware of where it came from.

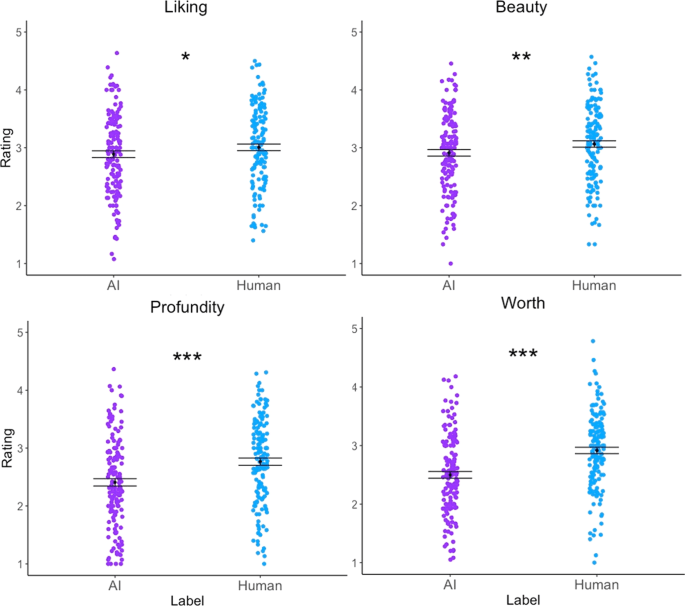

In this image, people are rating AI art vs Human art and I wanted to see if this would transfer over to music generated by AI as well. (From the study found at https://cognitiveresearchjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41235-023-00499-6 )

Technical Info

My data indicated a slight, however, constant difference in how the human subjects evaluated the musicality and the emotional content of the melodies produced by AI versus those produced by humans. The human subjects gave high scores to the technical quality (structure and rhythm) of many of the melodies created by the AI. However, when it came to the emotional aspects of the melodies (how they were perceived), the AI-created melodies did not score as high as those created by humans. The human subjects described the AI melodies as technically proficient but lacking an emotional impact.

In order to understand why there was such a difference in perception, I examined differences in the density of notes, the range of pitches and the amount of rhythmic syncopation in the two sets of samples. The melodies generated by the AI model were characterized by regular rhythms and typical melodic endings; features that are related to optimization rather than creative tension. In contrast, the human-generated melodies had variations in rhythmic spacing and phrase endings which resulted in higher emotional response ratings from the human subjects.

This implies that the neural sequence models generate the syntactical aspects of music, but do not produce performance level characteristics that suggest intent or emotion. It is those “micro-variations” of performance (e.g., slight time deviations or unusual harmonic changes) that listeners associate with the emotional qualities of music.

This understanding allowed me to improve my generator’s future versions. I began to test post-processing techniques to modify the velocity curve of the melodies, create rhythmic drift and reshape the melodic contours of the melodies based upon the reference data of human performances. The goal of these modifications is to decrease the gap between the expressive capabilities of algorithms and the creativity of humans.

My Conclusion

The study showed that emotion in music is not simply a pattern the model can learn but a relationship it must infer. AI can generate structure, but its meaning depends on human response. Data becomes creative only when interpreted, and that collaboration between system and listener defines the next stage of computational music research.